(MintPress) – As the world responds with shock as thousands of Palestinians are uprooted from their land by the hands of the Israelis constructing thousands of new settlements and attempts by the Burmese government to rid their land of the Rohingya people, a conflict waged against the native population in the U.S., just 150 years ago, goes largely without notice or remembrance.

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the U.S.- Dakota War, a dark time in history for relations between European Americans and Native Americans, ending with the largest public execution in U.S. history, as 38 Native Americans were hung. The remaining Dakota men, women and children were banished from Minnesota.

The war was more than a result of a clash between two cultures. It was a struggle between those who first inhabited the land and those who conquered it through colonialism. More than 1 million Native Americans lived on Minnesota’s land in 1862. And while their numbers were great, their way of life had been so forcibly transformed that many went hungry. Locked inside lands the U.S. government reserved them to, successful hunting opportunities became sparse.

“At the root of everything, factionalism was created when immigrants came to our way of living,” Dr. Clifford Canku of Sisseton Wahpeton community of Dakota told the Minnesota Historical Society in 2010. “And I think this factionalism was destructive to our people.”

Treaties signed with the U.S. government stripped Native Americans’ rights to their land. In return, the government promised, through treaties, yearly payments for occupied land. Annuities also included debt payments to European traders.

“Between 1805 and 1858, treaties made between the U.S. government and the Dakota nation reduced Dakota lands and significantly altered Minnesota’s physical, cultural, and political landscape,” it states on the Minnesota Historical Society website.

Yet as the Minnesota Historical Society indicates, many of those in the Dakota community felt as though debts had been increased arbitrarily by the U.S. government. Money intended for the Dakota people was instead directly handed to European traders. Native Americans saw this as a direct violation of their treaty, inflicting families and entire communities, who went hungry without recourse.

Little Crow, recognized as a representative of the Dakota, famously penned a letter to Col. Henry Sibley in the midst of the 1862 war, explaining the situation he and his people were in.

“We have waited a long time,” he wrote. “The money is ours, but we cannot get it. We have no food, but here are these stores, filled with food. We ask that you, the agent, make some arrangement by which we can get food from the stores, or else we may take our own way to keep ourselves from starving. When men are hungry they help themselves.”

Eventually, even the traders’ payments were cut off, severing the relationship with the Dakota, who also relied on the selling of goods for their livelihood.

In the face of hunger and limited resources, the Dakota people were bribed by the U.S. government to give up their traditions and way of life. With no other options, assimilation to European culture was a way for Native Americans to receive payment to feed their families. As a result, many attempted to rid themselves of their cultural identity, cutting off their hair and giving up the agricultural and hunting traditions of their people.

This, to many of the Dakota was unacceptable. And so, they waged war.

The war

The war began in August 1862 with an attack on a European settlement, resulting in the death of five Europeans. This sparked a movement among the Sioux Reservation, too, as a war was declared against the European settlers in an attempt to take back the land. Attacks on European communities persisted, resulting in an undocumented number of Sioux deaths and a documented 400 civilian deaths among the European community.

And so began the war.

On Sept. 26, 1862, before the military commission had even been compiled, General Pope wrote in a letter to Sibley stating his feeling toward the Dakota tribe, in general, referring to them as less-than-human — a group of people that should be cleared from the state.

“The horrible massacres of women and children and the outrageous abuse of female prisoners, still alive, call for punishment beyond human power to inflict. There will be no peace in this region by virtue of treaties and Indian faith. It is my purpose utterly to exterminate the Sioux if I have the power to do so and even if it requires a campaign lasting the whole of next year. Destroy everything belonging to them and force them out to the plains, unless, as I suggest, you can capture them. They are to be treated as maniacs or wild beasts, and by no means as people with whom treaties or compromises can be made,” Pope wrote to Sibley.

Pope went on to have a county named after him — Pope County — while Sibley was honored through the naming of Henry Sibley High School, in Mendota Heights, Minn.

Many of the Dakota fled from the state. Those who remained saw no other option other than to surrender. More than 1,000 Dakota people, including women and children, were held in the custody of the U.S. government.

“Some of our relatives in the Canku family were captured in 1862 and sent to Fort Snelling. There was nine of our family that were sent there. And then the rest escaped went to the Plains. They were implicated for being Dakota. Just being Dakota means that you were guilty before any consideration of being innocent,” Canku told the Minnesota Historical Society in 2010.

More than 800 of the Dakota then surrendered — a move that initiated 300 death convictions of Native  Americans through a military trial, ordained by Col. Henry H. Sibley, the same man who later, in 1863, led an excursion of more than 3,000 soldiers to rid the land of the Dakota.

Americans through a military trial, ordained by Col. Henry H. Sibley, the same man who later, in 1863, led an excursion of more than 3,000 soldiers to rid the land of the Dakota.

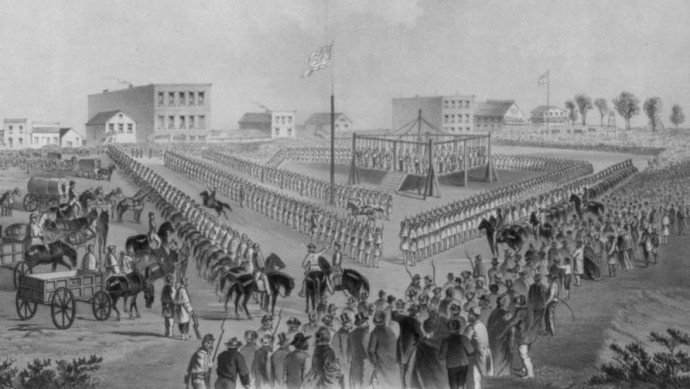

Not all of the convictions handed down through the military commission stood, however, resulting in the public hanging of 38 Dakota men in what is now known as Mankato, Minn.

The military commission that tried the Dakota men was unfair and biased, according to historians, as their punishments were being decided by the very people they attacked. Guilty or not, the opportunity for a fair trial was absent.

“The trials of the Dakota were conducted unfairly in a variety of ways. The evidence was sparse, the tribunal was biased, the defendants were unrepresented in unfamiliar proceedings conducted in a foreign language, and authority for convening the tribunal was lacking,” University of Minnesota Law School Associate Professor Carol Chomsky said.

The aftermath of war

After the hangings and banishment of the Dakota, the U.S. government sought to ensure that their threat had been erased. With rumors that some had remained within Minnesota, the military began an excursion to pursue the tribe.

Despite this, some Dakota remained in Minnesota. Others returned to the area in the 1880s, settling in Western Minnesota in what is now known as Granite Falls, Minn., where they created the Upper Sioux Community. It still remains today.

Today, Native American tribes in Minnesota retain the right to sovereignty under their reservation lands — this comes as a result of giving up the majority of their land to the U.S. government in the 19th century.

While given the right to solely conduct gambling operations on tribal lands, the plight of Native Americans in the state still exists. Native American communities have, however, been proactive in their approach to supporting one another. Fond Du Lac Tribal and Community College, for example, hosts the Minnesota American Indian Institute on Alcohol and Drug Studies Conference, a statewide gathering intended to “provide education on alcohol and drug abuse that addresses the total well-being of the American Indian individual, and community that is sensitive to cultural healing traditions.”