NEW YORK — The revelation that the Dow Jones industrial average and the Standard and Poor’s stock index closed at historic highs this past Thursday afternoon reminded me of an early autumn afternoon a dozen years ago in a glorious San Francisco apartment high in the sky.

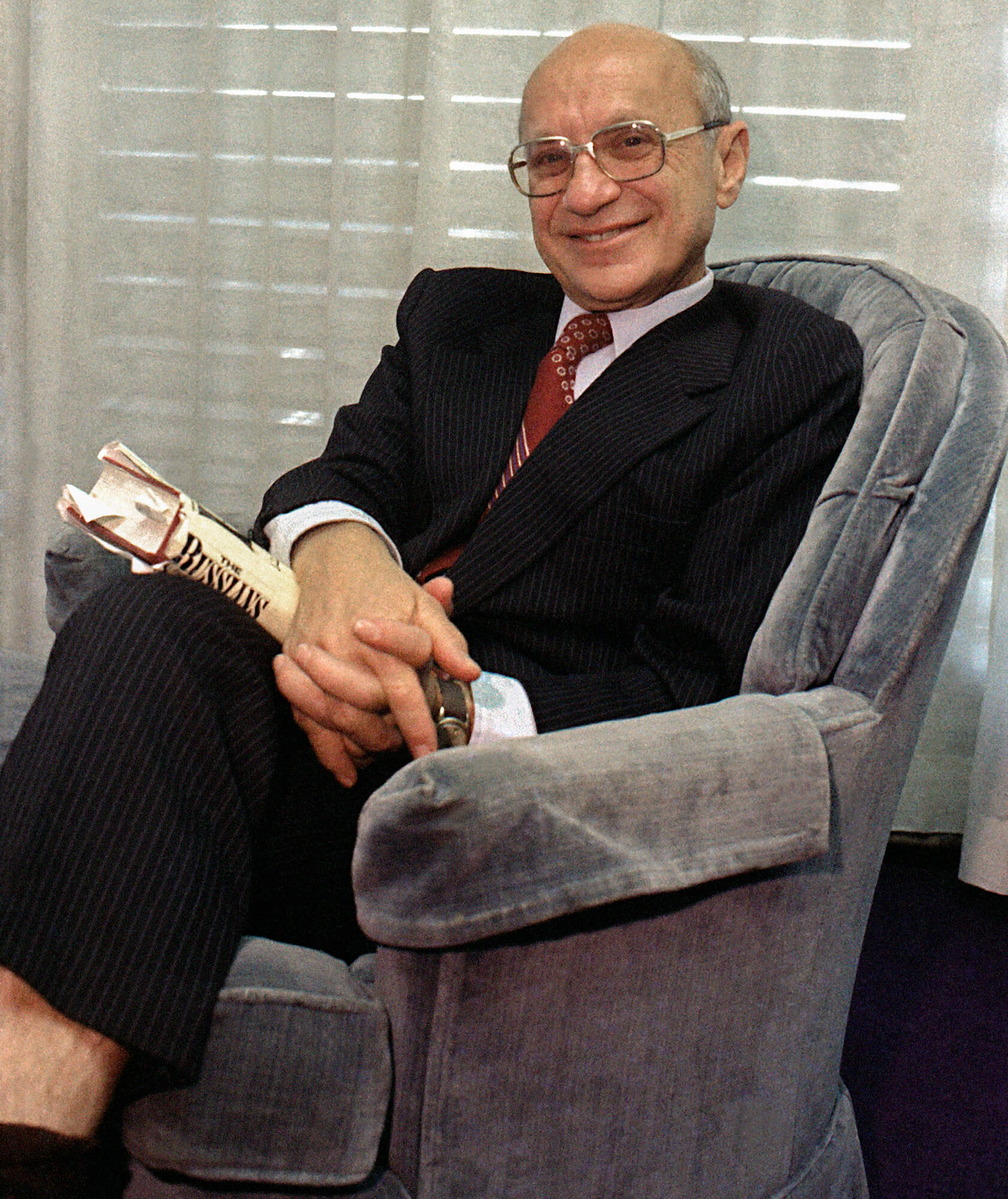

The apartment, perched atop a rise in the city’s Russian Hill neighborhood, belonged to one Milton Friedman, the Nobel Prize-winning economist who is widely recognized as the father of neoliberal economics. He’d granted my request to interview him for a book I was writing on one condition: I had to come to him.

With the San Francisco Bay and the Golden Gate Bridge shimmering in the distance like a champagne-colored fresco of sea and mountains and heroic steel beams, the 94-year-old Friedman leaned back in his chair, and offered his view of the world from where he sat, like Zeus on Mount Olympus.

These last 25 years have been wonderful, truly excellent in terms of the global economy. It’s been a period in which you’ve had a significant reduction in interference in trade, and the low inflationary environment has really created unprecedented opportunities for investment and innovation.”

It was two months before his death and as I sat and listened to him talk, I contemplated the iconic figure before me. He was much more pleasant than I’d anticipated — engaging and modest and sincere, from what I could discern. That he was hard of hearing made him a somewhat sympathetic figure, and his blunt-spoken manner and dogmatic libertarianism left the impression of a principled man who was wrestling honestly with the gravest issues of the day and had settled on what he genuinely believed was the best possible solution in an imperfect world.

I was struck by how nimble and energetic he was at his advanced age, and how absolutely tiny he was, a sprite of a man, barely breaking five feet in height. I was pondering the contrast between his physical stature and his towering presence in world affairs when a feeling of deja vu washed over me.

Six years earlier, in 2000, while reporting on the political unrest that had begun to envelop the southern African nation of Zimbabwe, I had sat down to an interview with Ian Smith in the living room of his sprawling home on the outskirts of the capital city of Harare. He was 81 at the time and I remember thinking how small he was — not diminutive like Friedman but gaunt, his chest almost caved in. When I was a teenager and read about Smith in the late 1970s, I imagined him a colossus, Africa’s Bull Connor, the prime minister of a country that had seceded from the British Empire and was known as Rhodesia.

As with Friedman, I had expected — wanted — to dislike him. But he was, in our meeting at least, a rather genteel man, white-haired and frail, a recent widower who seemed genuinely hungry for company and spirited conversation. He replenished my coffee cup whenever it was empty, and he invited me to stay and talk longer than the hour we’d initially agreed to. He said at the time of the country’s Black leadership:

This country has never seen such lawlessness and corruption. Blacks come up to me all the time and say that they were better off when I was prime minister. We had a fine country then, a strong economy that was the jewel of Africa. … Our Blacks were the happiest in the world.”

Much as Smith’s and Friedman’s sunny outlooks remapped the world that I knew — of declining living standards and poverty and immiseration and paychecks that always, always, ran out before months’ end — the Dow Jones and the S&P stock indices represent an alternate reality. For Africans living in Rhodesia — or workers in Chile, Egypt, the U.S., England or practically anywhere in the world — their words were not simply untrue, but the complete opposite of the truth as they experienced it. So with the numbers now peaking with the fortunes of the investor class.

In the brilliant light of Friedman’s apartment, it dawned on me that Smith and Friedman were one and the same, in a political sense: class warriors in the twentieth century’s twin imperialist movements, neocolonialism and neoliberalism, the goals of which were — are — one and the same: service to the empire and their own social class. They spoke for their constituents and no one else. They saw no gray and did not want to. The stewards of colonialism rallied their countrymen against the Communist menace, while globalization’s architects found their boogeyman in inflation and used it to bludgeon workers. The world they built and lived in was wonderful, not in spite of what had befallen Africans or Chileans or American workers but because of it. To the question of who gets ahead, the answer is almost exactly the same.

Balance lost, flying, falling, landing

Class war is a real thing and indices like the Dow Jones or the Nasdaq or the S&P reflect who’s winning, and who’s losing, like body counts from a battlefield. The One Percent’s accumulation of wealth that is reflected in an expanding stock market is a result of the dispossession of the 99 Percent. The white settlers of Ian Smith’s Rhodesia did indeed live fabulously, in no small part because of the hut tax they imposed on Africans to live in the land of their birth. The same can be said for investors in Friedman’s liberalized economies pouring trillions of dollars into predatory subprime housing loans.

The penultimate moment triggered by Smith and Friedman’s exploitation occurred 10 years ago this month when the investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed, producing the worst global financial meltdown since the Great Depression. Rather than address the structural imbalance that caused the crisis however, the political class doubled down in an attempt to re-inflate the burst asset bubble, showering the banks with cash. Jerome Roos wrote recently in ROAR magazine:

As governments across the globe bailed out their biggest banks and assumed the liabilities of the financial sector in a desperate bid to keep global capitalism from imploding under the weight of another Great Depression, they effectively transformed a private banking crisis into a sovereign debt crisis. From 2010 onwards, they then responded to this self-inflicted sovereign debt crisis with a policy of extreme austerity, rapidly slashing public expenditure to repay private bondholders – who often turned out to be the same financial institutions that had been bailed out with taxpayer money in 2008.”

This neoliberal approach to handling a dire economic downturn may soon produce a political crisis, reminiscent of the debt crisis that led to Hitler’s rise 80 years ago. And increasingly, the political class seems to be taking note. The stark inequality reflected in the soaring stock market and shrinking paychecks is unsustainable.

Gareth Porter wrote recently in TruthOut:

The two most powerful think tanks in Washington, representing center-left and center-right political elites, have responded to the populist shocks of the 2016 presidential election by trying to reposition themselves and the Democratic and Republican Parties as more sympathetic to populist concerns even while maintaining their attachments to the interests of big business and the complex of war-making.

The Center for American Progress (CAP), linked to the Democratic Party establishment, and the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), which is close to the Republican Party, have issued two long papers in recent months reflecting their high anxiety over the rapid growth of populism on both sides of the Atlantic — especially in light of the shocking success of both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump against Hillary Clinton and mainstream Republicans during the 2016 presidential election cycle.”

The U.S. seems headed inexorably towards its denouement, reminding me of the narrator’s refrain in the classic French movie, La Haine, or Hate, in which a young man tells a joke about a man who fell from a skyscraper, reassuring himself as he passes each floor: “So far, so good:”

It’s about a society on its way down. And as it falls, it keeps telling itself: «So far so good… So far so good… So far so good.» But it’s not how you fall that matters. It’s how you land.”

Top Photo | A Banksy art piece on Essex St, Chinatown, Boston. Chris Devers | Flickr

Jon Jeter is a published book author and two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist with more than 20 years of journalistic experience. He is a former Washington Post bureau chief and award-winning foreign correspondent on two continents, as well as a former radio and television producer for Chicago Public Media’s “This American Life.”