Ojibwe and Turtle Clan member, Dennis Banks, co-founder of the American Indian Movement, and a leader of the 1973 armed liberation of Wounded Knee, died at 80 years old surrounded by his family Monday.

Also referred to by his Ojibwe name, Nowa Cumig, the Indigenous resistance leader’s death was announced on social media and confirmed by his family to the Associated Press.

Cumig co-founded AIM in 1968 as the following year AIM members occupied Alcatraz Island to protest living conditions on U.S.-designated reservations and a host of other issues that Cumig would later describe as being “historic trauma” Indigenous people face due to contact with U.S. institutions and ethos.

The Indigenous leader was thrust into the national and international spotlight for his leadership role in the 71-day occupation and liberation of Wounded Knee, a town located on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota state. It was the site where U.S. soldiers had massacred hundreds of Indigenous people, including women and children, in 1890.

Speaking about the impetus to demonstrate at Wounded Knee, Cumig said, “it was aimed at trying to … bring about major change in America regarding policies, attitude, and the behavior of white America,” he said.

Debra White Plume, a Lakota water protector who was born on the Pine Ridge Reservation and participated in the operation, recalled, “Wounded Knee was liberated by relatives from the four directions.” She emphasized that their struggle, like others taking place in the 1960s and 70s, transpired due to Lakota people retaining their way of life and seeking to reclaim their land and the responsibility of caring for it.

“In the so-called border towns around us which we call occupied territory, Indians were getting killed and their murderers were not being held for justice,” she said, adding that men and women came to the conclusion that “enough was enough.” What followed was a “military occupation of our homeland,” which included FBI agents, marshalls and the army.

Two Sioux men were killed and hundreds more were arrested during the historic standoff. Cumig was acquitted of felony assault charges stemming from Wounded Knee. However, he was later convicted of rioting and assault and imprisoned for 18 months.

In the latter part of the 1970s he embarked on the Longest Walk, which saw him march from California to the U.S. capital of Washington D.C. over a five-month period. “It was a departure from the actions of Wounded Knee,” he told the National Museum of the American Indian, adding that “this time we would pledge to walk across without pipes, and it would be a great spiritual walk.”

More recently, Cumig has weighed in on demonstrations against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. “Historical trauma is still with us,” Cumig said adding, “When Standing Rock happened all this trauma” made hundreds of Indigenous nations say, “hey we are gonna go support them at all costs.”

Faced with continued institutional racism and oppression, Cumig said the coming together of the nations under one, unified flag was “beautiful,” something he hadn’t seen in his “entire life.”

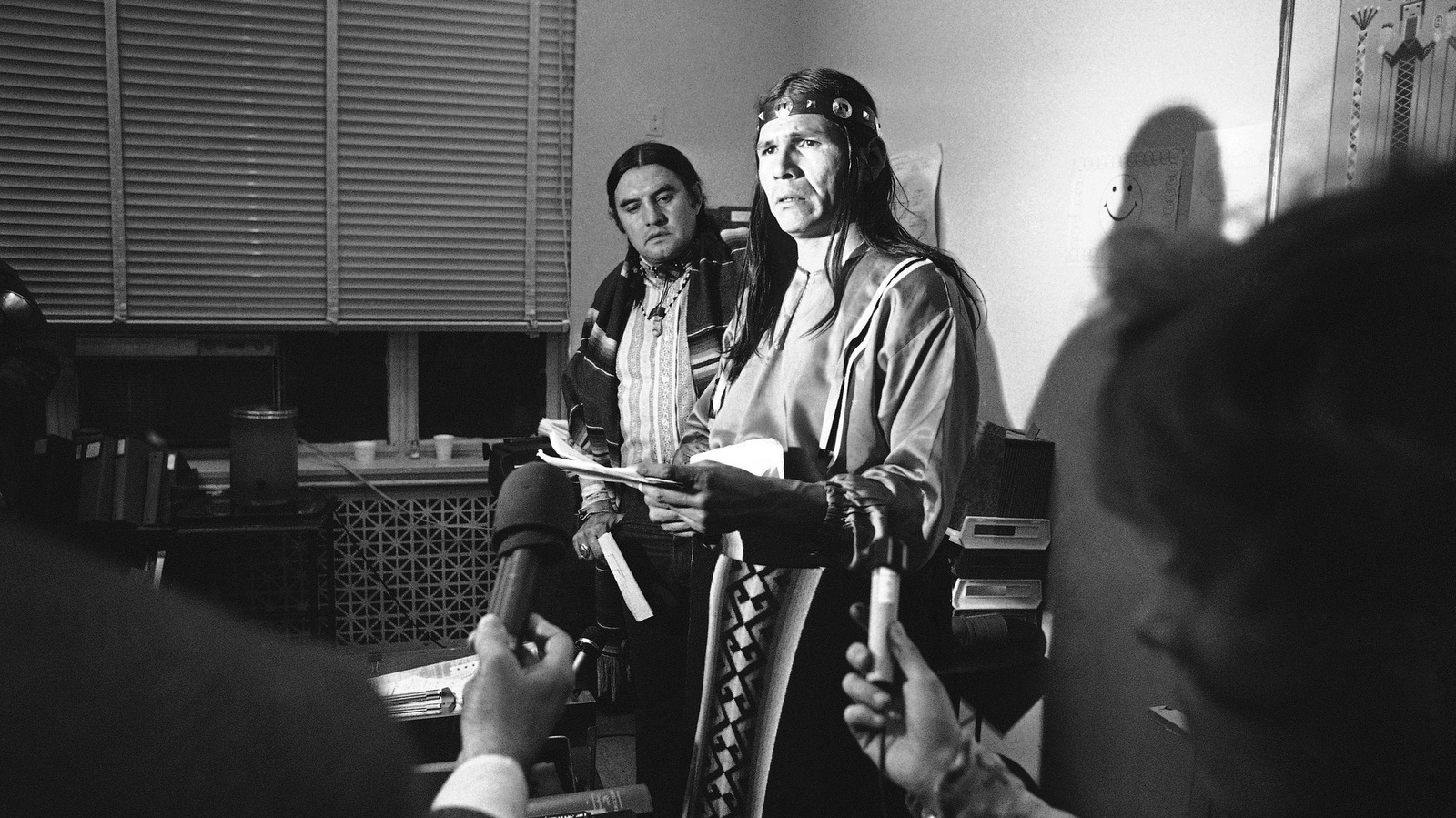

Top photo | Dennis Banks, field director for the American Indian Movement, right, and Vernon Bellecourt, another Indian leader, announces that Indians will be allowed to hold religious services in Arlington National Cemetery to honor their war dead buried there, Nov. 5, 1972 in Washington. The announcement came after an appellate court reversed a District Court ruling which barred the action. (AP Photo/Jim Palmer)