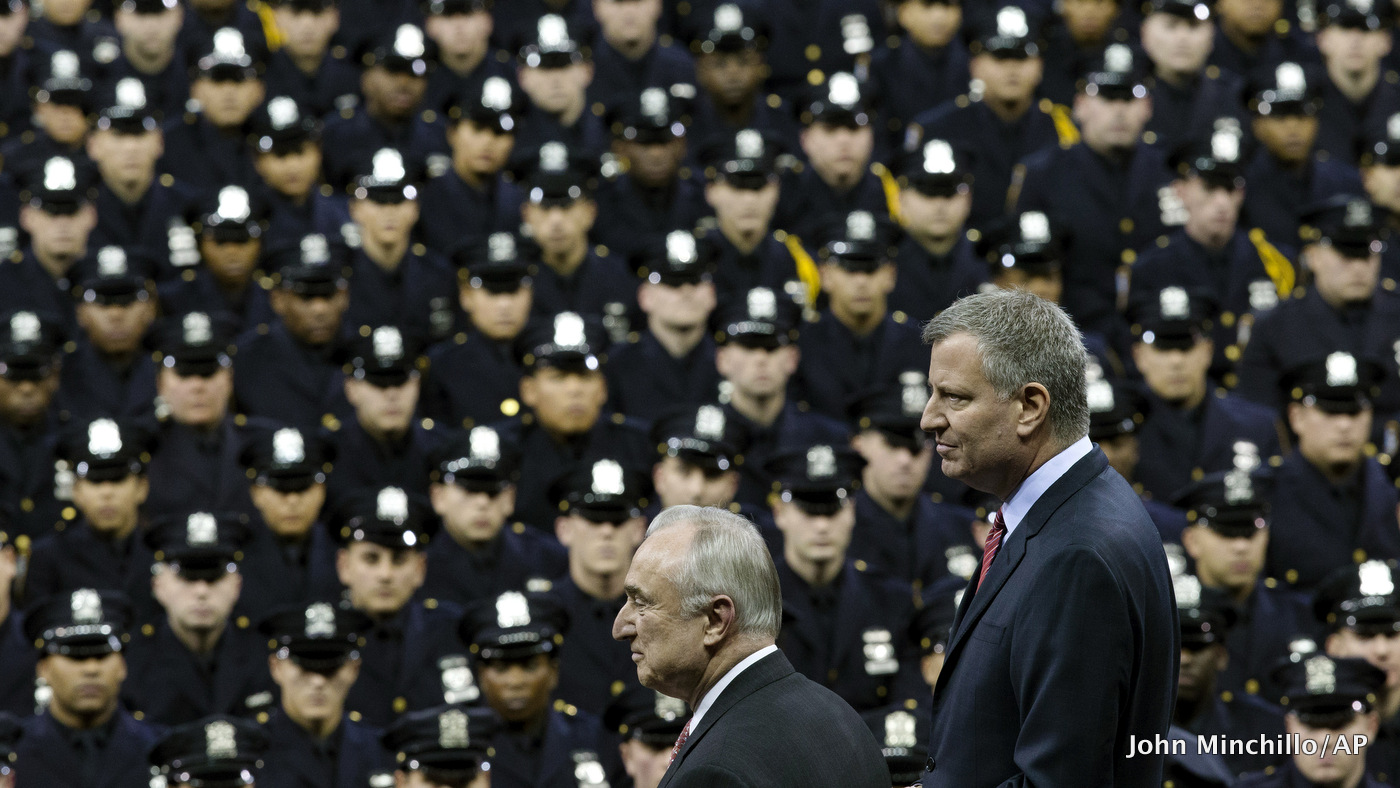

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, right, and NYPD police commissioner Bill Bratton, center, stand on stage during a New York Police Academy graduation ceremony at Madison Square Garden in New York. Mayor Bill de Blasio declares he has moved past the crisis with police that threatened to derail his administration. He says in an interview with The Associated Press that he was able to pull off the feat sticking to a strategy to maintain the moral high ground and avoid confrontation with police unions. At the same time, public opinion turned against police for their behavior in the feud, including turning their backs on the mayor.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, right, and NYPD police commissioner Bill Bratton, center, stand on stage during a New York Police Academy graduation ceremony at Madison Square Garden in New York. Mayor Bill de Blasio declares he has moved past the crisis with police that threatened to derail his administration. He says in an interview with The Associated Press that he was able to pull off the feat sticking to a strategy to maintain the moral high ground and avoid confrontation with police unions. At the same time, public opinion turned against police for their behavior in the feud, including turning their backs on the mayor.

NEW YORK — On Tuesday, Joel Edouard, an officer with the New York Police Department, appeared in Brooklyn Supreme Court on a misdemeanor charge of assault and an official misconduct charge for apparently stomping a subdued suspect in the head on July 23.

Jahmiel Cuffee was allegedly consuming alcohol and rolling a joint on the sidewalk. Cuffee allegedly tossed the contraband when he saw officers approaching and then resisted arrest. After other officers had subdued Cuffee on the ground, Edouard kicked him in the head.

Cuffee was ultimately arrested for attempting to tamper with evidence, obstructing governmental administration and resisting arrest, but all charges against him have been dropped.

In court, Edouard’s attorney argued that his client was attempting to arrest Cuffee — he was just doing his job.

This is the third time since November that a police officer has been indicted for excessive force the Brooklyn DA’s Office. This case, which took place just a week after the July 17 chokehold death of Eric Garner at the hands of the NYPD, and the officer’s resulting court appearance highlights a growing trend of strife between the NYPD, the public and the New York City Mayor’s Office, which was epitomized by a three-week virtual work stoppage by the NYPD, in which most precincts only made essential arrests.

The policing slowdown cost the city between $3 million to $5 million in lost ticket revenue and fines. Traffic violation citations were down 94 percent from the year prior, drug arrests down 84 percent, parking violations 92 percent and low-level offense summons 94 percent.

The exact cause and cost of the slowdown, however, may be harder to calculate beyond political rhetoric. The slowdown and the deaths of Officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos also effectively de-emphasized the public protests regarding the apparent rash of unprosecuted police-involved deaths of black males nationwide and the national discussion about the relationship between law enforcement and communities of color.

Collectively, these incidents reflect a law enforcement community in crisis. The availability of cellphones and video cameras has made it easier to record police interactions with the public and to cast a critical eye on suspected malefeasance. This has created tension between the public’s expectations of what is acceptable behavior among law enforcement and law enforcement’s expectations of being able to do the job asked of them without recrimination.

This, at its core, is a classic labor struggle between law enforcement and government in which questions of policy and perception come in direct conflict with a police officer’s right to do his job without the risk of public shaming. In the midst of this struggle there are also questions of public safety and the authoritative role of the police that extend not only to the NYPD, but to police departments nationwide.

“Community members want to reside in safe environments, but to achieve this, they expect the police to conduct their jobs in a legitimate manner,” said Daniel Lawrence, a research associate with the Justice Policy Center of the Urban Institute, to MintPress News. “Independent of the offense that leads to the police encounter, be it an assault or selling loose cigarettes on the street, the officers are expected to approach and conduct themselves in a professional and respectful manner.”

Explaining that people aren’t upset that officers are making arrests for petty offenses, he said, “They are upset because the cases that most of society know about are those where the officers conducted themselves in a way that is counterintuitive to how authority figures should behave.“

The NYPD and the racism question

While in-fighting between the NYPD and the mayor’s office predates the de Blasio administration, this latest round of bickering is unique in that it doesn’t immediately center around contract negotiations or benefit cuts. Rather, the nexus of the most recent fight was public frustration with a Staten Island grand jury’s decision not to prosecute Officer Daniel Pantaleo for the administration of a chokehold on Garner, which contributed to Garner’s death.

While questions remain about whether Pantaleo employed an acceptable tactic to subdue Garner, this event highlighted a continuing issue surrounding the NYPD and race. In December, Reuters published the results of interviews it conducted with 25 black male NYPD officers, 15 of whom are retired and 10 on active duty. All but one reported that they had been subjected by racial profiling by police while they were off duty.

The officers indicated that they were pulled over for no obvious reason, subjected to “stop and frisk” while shopping, and had their heads slammed against their cars. Five reported having guns pulled on them. Of the one-third who indicated that they reported the incidents to their superiors, all but one indicated that the case was ignored or they faced denial of overtime, promotions or assignment choice.

The report reflects the persistent issue of the NYPD’s inherent bias against black males. According to the 2010 New York State Task Force on Police-on-Police Shootings, 10 of the 14 officers killed in police-on-police shootings from 1995 to 2010 were from communities of color. The last time a white, off-duty officer was killed in a mistaken-identity, police-on-police shooting in the United States was in 1982.

“We find the scientific evidence persuasive that police officers share the same unconscious racial biases found among the general public in the United States,” read the report. “Specifically, we are persuaded by evidence that both police officers and members of the general public display unconscious biases that lead them to be quicker to ‘shoot’ images of armed black people than of armed white people in computer‐based simulations testing shoot/don’t‐shoot decision‐making.”

Understanding implicit bias

New York City police officers stand guard outside the building that houses Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp headquarters in Midtown Manhattan on Friday, Jan. 16, 2015. In the wake of the Paris terror attacks in early January, New York’s Police Department is quietly expanding training for what it sees as the latest terror threat teams of «active shooters» who arm themselves with high-powered rifles and open fire.

New York City police officers stand guard outside the building that houses Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp headquarters in Midtown Manhattan on Friday, Jan. 16, 2015. In the wake of the Paris terror attacks in early January, New York’s Police Department is quietly expanding training for what it sees as the latest terror threat teams of «active shooters» who arm themselves with high-powered rifles and open fire.

The fact that one has an implicit bias is not necessarily a bad thing. At its core, the human brain is a difference engine; it makes automatic calculations between what it perceives and what it knows, then forges conclusions from this. For example, if one looks at an unfamiliar piece of furniture and reasons that it resembles a sofa, the obvious conclusion would be that it is safe to sit on.

However, implicit bias can become a negative if implicit attitude taints how a conclusion is drawn.

As quoted by Captain Tracey Gove of the West Hartford, Connecticut, Police Department in a 2011 article for Police Chief Magazine, “‘[I]f we think that a particular category of human beings is frail — such as the elderly — we will not raise our guard.’ Also, ‘[I]f we identify someone as having graduated from our beloved alma mater, we will feel more at ease.’ Lastly, when introduced to someone new, about whom nothing is known but who is reminiscent of an old, admired friend, one may instantly feel comfortable and at ease with that person.”

According to data gathered from the 2,355,303 volunteers who took Harvard University’s Race Implicit Association Test from 2002 to 2012 — which measures the implicit bias a person may have against a particular race — the majority of white Americans have a demonstrated bias against blacks. Fifty-four percent of all respondents had a strong or moderate automatic preference to white people over black people, compared to just 6 percent that had a strong or moderate automatic preference for black people over white people.

This bias is strongest in states with historic trends of racism, such as those in the South, the Midwest and the mid-Atlantic. As the volunteers who took the test are more liberal, better educated, younger and more likely female than the American population as a whole, it is likely that these results actually underreport the nation’s implicit bias.

If the perception one has of a particular socioeconomic group is overwhelmingly negative, it will color one’s attitude toward that group, even if that person is not aware of the attitude shift. With the perception of black and Latino males being overwhelmingly negatively slanted by media depictions — with few positive depictions being available — there is a pervasive bias in play. Yet because this is a bias in attitude and not in conscious thought, it is difficult to diagnose or correct, even among those consciously seeking to address it.

As such, it is safe to assume that the majority of police officers carry the same bias. While not every police situation involving a black male is racially-tinged, the public perception is that it is. It is this issue of perception that presents the greatest challenge for police today.

“When dealing with perceptions, the question of justice comes into play — was justice served, was what happened just and justified?” said Tod Burke, associate dean and professor of criminal justice for the College of Humanities and Behavioral Sciences at Radford University, to MintPress.

Explaining that an officer’s actions can always be analyzed and debated after the fact, Burke noted that “it is difficult to determine what the officer saw or was thinking in the moment. The question is — considering that the officer only has a split second while in the field to make a potential life-or-death decision — does the officer have the training and understanding he needs to do his job effectively?”

He continued:

“Simultaneously, we must take care that our search for justice doesn’t yield injustices. It’s unfair to make an officer who was doing his job properly a scapegoat to the community’s call for justice. Most individuals that choose to be officers are honorable people who feel that they are serving their communities. It is important that the bad cops are sorted out and the good cops are given the tools and support they need to serve the public’s will.”

Policy and the police

Yet this does not explain why so many in the NYPD personally blame Mayor Bill de Blasio for the public backlash the department has received following the Garner case. “The mayor’s hands are literally dripping with our blood because of his words actions and policies and we have, for the first time in a number of years, become a ‘wartime’ police department,” said Pat Lynch, president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, which represents NYPD officers under the rank of sergeant.

This rhetoric is thought to have contributed to the slowdown. The New York Times reported on Tuesday Jan. 6: “For the seven days ending Sunday, officers made 2,401 arrests citywide, compared with 5,448 in the same week a year ago, a 56 percent decline. For criminal infractions, most precincts’ tallies for the week were close to zero. Citywide, there were 347 criminal summonses written, compared with 4,077 in the same week a year ago, according to Police Department statistics. Parking and traffic tickets also dropped more than 90 percent, the statistics showed.”

The halt to non-essential arrests and ticketing occurred in the wake of the deaths of Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos, two NYPD officers shot while they were on duty in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn on Dec. 20. Liu and Ramos were killed by Ismaaiyl Abdullah Brinsley, who some sources allege chose the officers at random in revenge for Garner’s death in July.

Following conciliatory comments New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio made to the community of color on Dec. 2, following the failure of the Staten Island District Attorney to seek prosecution against the officers involved in Garner’s death, the NYPD — encouraged in part by the various police unions that have called on their members to take extra steps to ensure their safety — has actively protested the mayor, with hundreds of officers repeatedly turning their backs to de Blasio as he spoke at Liu’s funeral. In his comments, de Blasio recalled telling his son — who is biracial — to be cautious of the police.

“There’s that fear that there could be that one moment of misunderstanding with a young man of color and that young man may never come back … It’s different for a white child. That’s just the reality in this country,” de Blasio told George Stephanopoulos on ABC’s “This Week” in defense of his original statement. The unions have taken the comment out-of-context to suggest that the mayor is accusing the NYPD of being racist and not looking out for the officers on the street.

Meanwhile, Lynch has been accused of flaming tensions as a tactic toward forcing the city to give in to union demands in ongoing contract negotiations. However, this sentiment has trickled down to many officers on the street. One theory why this may be can be seen in the city’s administrative summons, or “quality-of-life” violations.

City authorities, including the NYPD, issues thousands of court appearance summons every day for administrative rules violations, such as drinking alcohol on the streets or being in a public park after dark — violations which have no corresponding illegality under New York state law. The issuance of such citations, which typically involve a $25 to $100 fine, increased since the “broken windows” policy of busting small offenses to prevent the escalation to larger offenses started in the early 1990s — from 160,000 in 1993, as reported by the New York Daily News, to a peak of 648,638 in 2005. Although the number of these “broken windows” tickets issued has dropped — down 17 percent last year — these citations remain the primary activity for the NYPD.

According to a New York Civil Liberties Union calculation based on data from NYPD summons forms, approximately 85 percent of the 6 million-plus New Yorkers cited with violations between 2002 and 2013 were either black or Hispanic, based on available demographic information. Additionally, the primary locales for these “nuisance” tickets are black or Latino neighborhoods, with 18 of 20 of the neighborhoods with the most summonses under the administration of former Mayor Michael Bloomberg being majority black or Latino

“New York is a multiracial city, but judging from the faces in cramped courtrooms, one would think that whites scarcely ever commit the petty offenses that lead to the more than 500,000 summonses issued in the city every year,” Brent Staples wrote in a 2012 The New York Times editorial.

While these citations are not criminal in their nature, not appearing at summons court for them is. Failure to appear leads to arrest and an appearance in criminal court, resulting in the existence of a criminal record that will endanger an individual’s chances toward having a citizenship application denied, increase the likelihood of employment discrimination, or disenfranchise one to the availability of government and social benefits.

This has raised concerns that police are using these disorderly conduct summons as a catchall for stops that otherwise have no rationale. The high dismissal rate of summons cases that actually appear before summons court led a civil rights suit, Stinson v. City of New York (filed May 25, 2010), alleging that the high summons rate is due to departmental quotas and that it has the net effect of violating the constitutional rights of the cited and subjecting them to lost work and school time and pointless arrest.

From the police officer’s perspective, however, he is just doing his job. If he fails to meet his quota, he may be punished or fired. This puts the officer in the difficult position of defending and enforcing policy he may not agree with or that could make the community turn against him. Because of this, there is an unspoken agreement between police and politicians — a hangman’s truce of sorts — in which the police willingly enforce the politicians’ policies if the politicians give them the freedom to do the job without critique.

This is likely why de Blasio’s comments struck a nerve among so many cops. Much of what an NYPD officer does has nothing to do with law and order, but the enforcement of City Hall policies. Many officers saw the comments as a betrayal, criticism for doing a job they did not sign up to do in the first place.

In light of not only the Garner chokehold death, but also the Ezell Ford shooting in Los Angeles; the John Crawford shooting in a Wal-Mart near Dayton, Ohio; the shootings of Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Ohio, Andy Lopez in Santa Rosa, California, Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Akai Gurley in Brooklyn; and the fatal botched traffic stop of William Corey Jackson in Geneva, New York, there is a clear need to redefine what is expected from the modern police officer.

“Legitimate policing consists of specific behaviors that officers exhibit while interacting with community members,” said Lawrence, of the Justice Policy Center of the Urban Institute.

“Today, experts are recommending hiring a new type of officer,” he said. “A strong police officer today is one who fits to the dominant reform model of the past 30 years — community-oriented policing.”

He pointed out that the best model for new officers is one that promotes the fair and respectful treatment of community members of all backgrounds.

“Modern officers can help build community relationships by being polite and respectful, taking account of an individual’s needs and concerns, acknowledging people’s rights, allowing the community member to share his or her concerns, actively listening to those concerns, and being unbiased in their decision.”

There must also be a recognition of the role of policy enforcement in policing. According to Radford University’s Burke, the consequences of policy must be considered before policy is implemented. If, for example, police were to increase the number of terry stops for weapon infractions, one must consider where likely the majority of these stops will occur, who is most likely to be stopped, and if the policy is likely to aggravate existing tensions between law enforcement and these communities.

Furthermore, a mechanism to discuss these concerns between all parties involved must be created. While the public increasingly sees the police as an out-of-control force which relies too much on excessive force, the police see themselves as the victims of policy they are not free to change and are compelled to enforce. If reform is to happen, all three players — the public, the police and the politicians — must be willing to sit down and discuss the problems at hand, free of allegations or hurt feelings. Without this, any attempt at correcting the state of law enforcement would constitute a surface correction, at best.

“Everyone wants to be heard and no one wants to be bullied,” added Burke. “The police just as much wants their voices to be heard by the administration as the public wants to be heard against perceived injustice.”

“What is needed, more than anything else, is to bring the community back together and a reminder that the police are a part of the community, as well.”