From my apartment window high up in the Hyatt Galleria, I had an amazing view of Dubai’s skyline and the Gulf waters. The only building taller than the Hyatt was the Dubai World Trade Center, which I could see off in the distance. Looking out my window at the world below, it wasn’t difficult to understand why I was so happy to be here. Done were my days of living in a one-room apartment on the first floor of a dilapidated building in the center Cairo. Now that I had finally gotten the attention of my editors, I was sure there was no turning back.

It didn’t take me long to recognize that there was another side of Dubai that was far less glamorous than the one I was living. I got a glimpse of it the evening I arrived at the airport, but because it was all so new to me, I didn’t see beyond the beautiful colors. In a previous segment I referred to the throngs of people waiting in line at immigration as a “fashion show at the United Nations.” In reality, they were the indigent side of Dubai; the ones forced to leave their country, home and family in search of work at any cost.

Even today, they go only to work — and do nothing else — from as far away as the Indian sub-continent, the Far East, Africa and anywhere else there is an excess labor pool desperate to get out. Tempted by agents and or middlemen who promise them good wages and a better life; they are handed tickets and put on planes to the UAE and the other Gulf countries to fill a demand for laborers. In reality, many of the workers who go, literally do so knowing very well that they won’t return home for many years. Many give up their wages for the first, second and sometimes third year to the agents as payment for bringing them to the Gulf. Once in the Gulf, they are poorly paid, housed in overcrowded accommodations and forced to work long hours under the harshest of conditions. It isn’t hard to spot them because they are everywhere — on all the construction sites, cleaning the streets and working as domestic help, to name a few.

This is the part about Dubai that has bothered me from the very beginning and it didn’t take me long to see that behind the façade there was (and is) an ugly side to this “Economic Miracle of the desert.”

Camel racing

As I mentioned in my previous entries, we rarely left the Hyatt compound during the daylight hours unless it was to go to the helipad at the airport. However, there were times when we heard about a story that just sounded too unusual to pass up.

I guess you could say that CNN’s Jim Clancy was bored spending his days sitting in the makeshift bureau monitoring ship traffic on the emergency band radio while we were off flying out over the Gulf in our helicopter. One Friday shortly after I arrived, Clancy told his crew that he wanted to do a story about camel racing. After discussing it with my editors in Paris, I decided to go along. In the end, my colleague at Associated Press, the CNN crew and myself abandoned the bureau for a morning to go and cover the races. Clancy was convinced that we’d be the only press there and that it would make for a unique and interesting story away from the “tanker war.” And besides, it was the opening day of the camel racing season.

In the middle of October, the temperature and humidity are still relatively high, so most sporting events at that time of year take place at night or very early in the morning. Camel racing is no exception, so in order to get to the track before the first race, we had to leave the Hyatt compound long before sunrise.

The five of us piled into my subcompact Toyota rental car with all our gear and headed out into the desert. After an hour drive, we arrived at the track, and the first thing we noticed was that we were not alone. Somehow every other television news crew based in Dubai had thought about doing the very the same story.

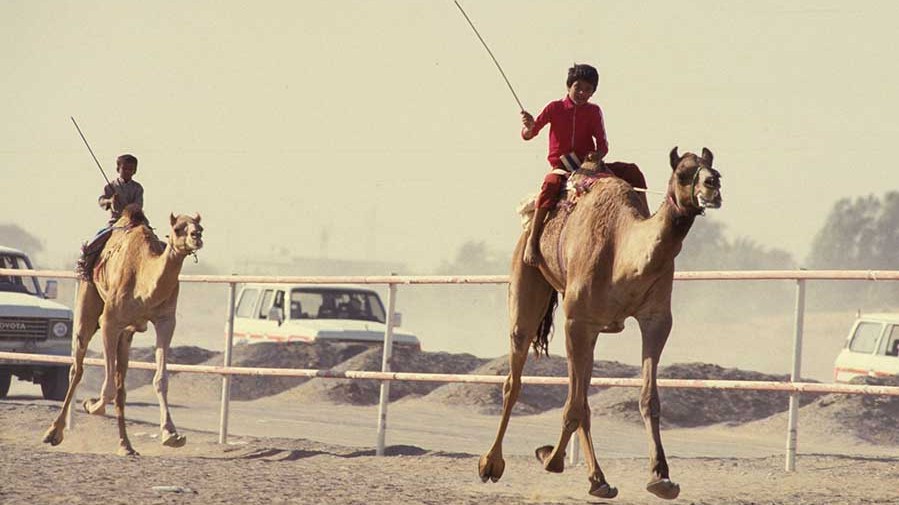

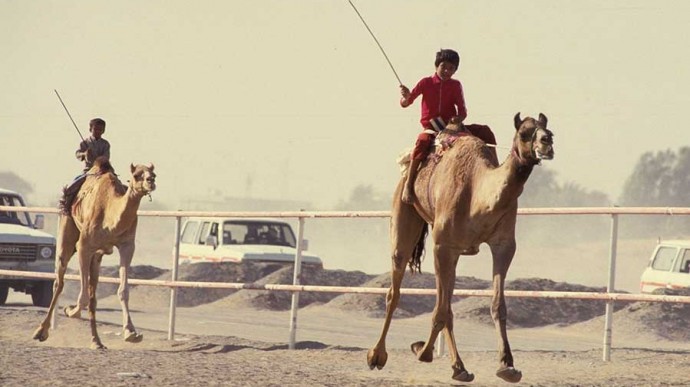

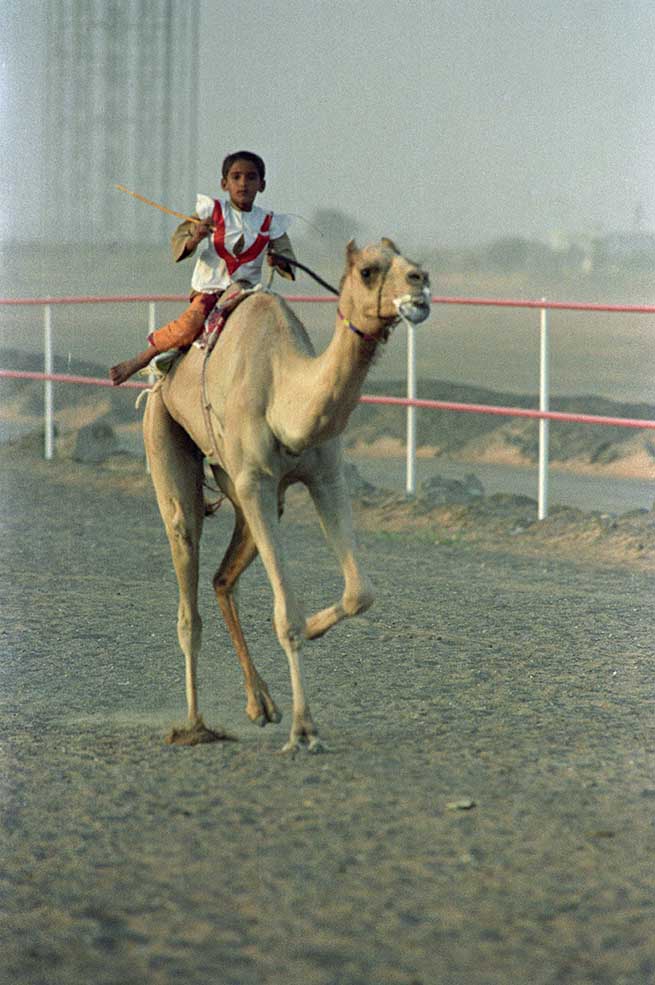

There was pandemonium everywhere. The Emirati camel owners were beside themselves with excitement to see the international press for what was normally a very local event. Camel drivers jostled with Range Rovers, Land Cruisers and spectators to get their camels into position while trainers and camel owners yelled out instructions to the child jockeys as they were getting readied and Velcro-attached to their saddle for the opening race. In the middle was the press, recording all the sights and sounds.

One local Emirati got so enthusiastic by all the attention that he jumped into his Toyota Land Cruiser and stated racing up and down the sand dunes, sending his vehicle flying into the air. Filled with adrenalin, he decided to attempt the impossible and climb a particularly steep dune, which was slowly engulfing a wooden hut used by Pakistani workers at the track. About half way up, it obvious he wasn’t going to make it, so in an attempt to save the Toyota from rolling over, he turned the wheel sharply. But instead of coming directly down, he veered a little and came crashing right through the roof of the hut.

After numerous unsuccessful attempts by the crowd gathered to dislodge the Land Cruiser from the hut, the Emirati got fed up and began cursing at the poor Pakistani laborers whose house he destroyed, and finally stormed off into the desert — or so we thought.

Once the dust settled and the novelty of our presences wore off, it was time to get down to business and start the first 6 km race of the day.

As much as I was caught up in the racing euphoria, it wasn’t difficult to see that there was something seriously wrong.

Camel racing goes back nearly 200 years and is popular throughout the entire Gulf region. A prized racing camel can fetch anywhere from $100,000 to upward of a million dollars.

Camel jockeys

As recently as a decade ago, camel jockeys were all children (some reportedly as young as three) that were taken from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Sudan. Most of the young boys were rounded up in very poor regions, often with the consent of their  parents for a fee and smuggled into the Gulf states. Once there, many of the boys were housed in miserable conditions with inadequate sleeping and/or toilet facilities.

parents for a fee and smuggled into the Gulf states. Once there, many of the boys were housed in miserable conditions with inadequate sleeping and/or toilet facilities.

There are numerous documentaries and human rights reports that show the horrific conditions many of these boys endured during their time as camel jockeys. In order to keep the boys’ weight down so that the camels could run faster, some of the boys were deprived of food. Independent observers reported numerous cases of children being beaten, and worse, raped by the men hired to look after them. Then there are the boys who never made it back home because they fell off the camel and were trampled to death.

In 1993, there was a push in the UAE to stop the practice of using children, but it didn’t actually come into effect until 2002. The UAE was the first to ban the practice followed by the other Arab Gulf countries. Today, the minimum age for a camel jockey is 15.

The races

In order to get the best shots of the race, I hopped in the back of one of the Emirati’s Land Cruisers so that I could be close to the action. The Emirati camel owners drive their 4x4s on a separate track alongside the camel racetrack so that they can follow the race and at the same time shout instruction to the jockeys by way of walkie-talkie. Most of the children had walkie-talkies attached to their chest.

Even though gambling is illegal in the Emirates, it didn’t stop the Emiratis from waging bets on the side.

The race starts with roughly a dozen camels in a line. Behind each of the camels is what I call a chaser (I don’t know the official name) who yells, screams and hits the camels with a stick to get them moving at the very beginning of the race.

As the camels jostle for position, so, too, do the Emiratis behind the wheel of their 4x4s. At the very beginning, it’s almost as if two separate races are taking place at the same time. Within a short span of time, the camels spread out and by the end of the race there is rarely a “photo-finish.”

After watching a few races, we all decided to call it a morning. As we were packing our gear and preparing to leave, guess who shows up in a brand spanking new Land Cruiser? The Emirati who crashed his last car through the roof of the hut.

In a desperate attempt to get our attention all over again, he began honking his horn and waving his arms as he raced across the desert. Unfortunately for him, it was too late and, by now, too hot. The only thought going through my mind (and I’m sure the other media present) was to take a dip in the pool back at the Hyatt.